(Kütiorg is a remote valley in South Estonian woods, where Laurits lived 1967–2009.)

KÜTIORG

It isn’t very difficult for me to recall Kütiorg (Hunter’s Valley). I don’t even have to close my eyes to do that. I lift my gaze above the dinner table and look at Evenings in the Woods hanging on the wall. That is Kütiorg, probably photographed from the balcony of the Laurits’s little house or from the upper slope in front of the house: fir trees march down the hill slopes into the valley row on row, curtain after curtain, but the horizon is left unfinished. The world transforms smoothly into seemingly absentminded fog. Everything dissipates and somewhat resembles the lines written by Pessoa,

“To be without a single emotion, a single desire, a single wish

rather to simply be, in the perceptible air of things,

abstract awareness with the wings of thought”.

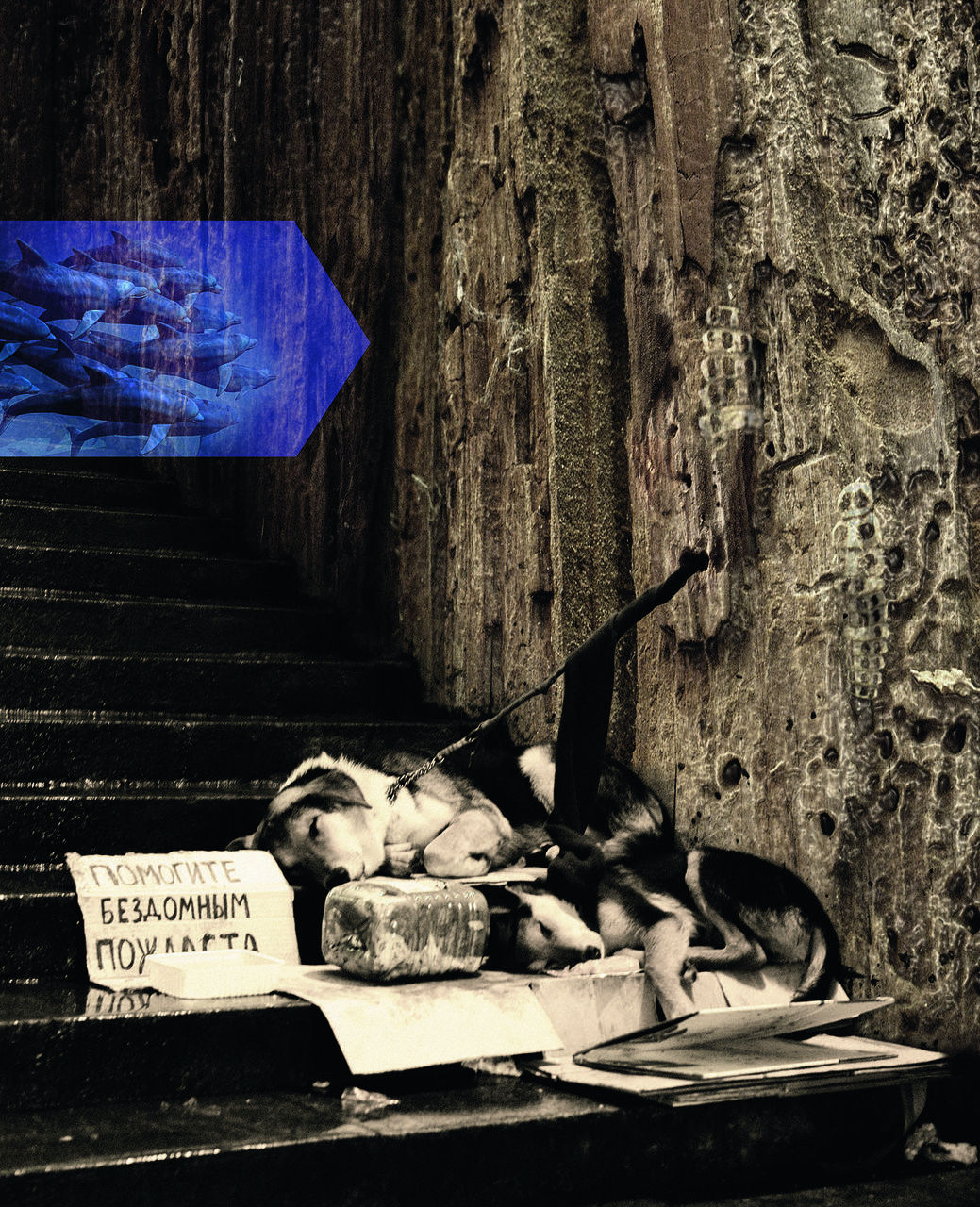

In the foreground of the picture, however, are the heroes of Soviet outer space mythology, Belka and Strelka, the eternal vagabonds and the Cerberuses of the universe, who Laurits finds years later on the streets of Moscow lying beside a beggar – back home but incognito and keeping silent about what they have seen.

I don’t know what Peeter wants to say through this picture because I’m not sure if he wants to speak in his own name here at all or if he is performing the same operation that he attempts in so many of his works – and particularly during his so called Kütiorg period: to liberate himself from his “ego”, to step away from himself, to disappear from the trap of consciousness, to turn into dust under the sofa of eternity. Perhaps he isn’t even the one who made this picture. Maybe it was Kongo instead – a German shepherd with a liberal view of the world yet with unwavering principles for whom moving with the Laurits’s from the city to Kütiorg was not movement to a new place but rather a return, arriving back home to a home where he had never been before. He often lay on the balcony of the little house with his head on his paws and eyed the valley, framing its composition more or less the same way as in this picture. Peeter often spoke with him: about unfinished housework, signs of nature, or love affairs. Yet alongside chats on everyday matters, I have also heard conversations where Peeter treated Kongo as a mailman between this world and poetry, asking the dog about dreams and secret paths. These things interested Peeter. He often allowed his animals to direct him around in the woods (a parallel here to Francis of Assisi is nevertheless inappropriate). Thus we need not offhandedly discard the hypothesis that the storyline of Evenings in the Woods is not Peeter’s picture but rather one of Kongo’s many dreams, framed in a scenery motif from the art of classical painting and coated with Kütiorg green, that dark green colour of the thick, sodden mass of moss that proliferates throughout Kütiorg in the summer and has overrun a large part of Peeter’s works that have been completed in Kütiorg. This is because there is some kind of particular higher state of being in that green: it is not merely photosynthesis or the greenery of nature. Instead it is a green that in its proliferation resembles the threatening and nurturing ocean, where everyone who stands on its shores starts feeling like a tiny speck.

Yes, it is not difficult to recall Kütiorg. I found myself there for the first time some ten years ago. By then Peeter had been living there for a few years already. Yet until then he had lived his whole life in Tallinn. Interspersed detours and stops elsewhere were generally speaking short term and nobody knew to expect his move to the countryside. Rumours and insinuations have painted a picture for me of the Peeter of the 1990’s as an urbanist joker for whom the enjoyment of the benefits of burgeoning civilisation was a part of the art of living. In an interview conducted many years ago, he talks about his exotic dishes that reportedly surpassed the menus of most of Tallinn’s restaurants. He could often be seen in the theatre and in movie theatres, to say nothing of the openings of exhibitions and frenzied parties. There were always people around Peeter. His departure from the city came as a surprise to many. No explanation was found for it. Why did Laurits suddenly start living in a house with strange, spontaneously generated architecture built as a summerhouse that he bought from his teacher? Surviving the first winter there was something of a minor miracle because the house did not have proper stoves or hot water, the electric current was weak, the wind quickly piled drifting snow on the access roads, cutting them off for long periods of time, and the nearest neighbours were several kilometres away. Some tried to make sense of it through Ibsen. They said you can be truly free only in complete solitude, yet the breaking points still remained visible – something happened in Laurits’s life and creative work. Neither was quite the same anymore. And at the same time, it was only in Kütiorg that Laurits tied together some important focal points that he had already started on in the 1980’s but had left open until then.

Kütiorg is located in Southern Estonia. It takes about four hours to get to the county’s central town from the capital by bus and you can carry on from there by local bus or taxi. Yet the final kilometres have to be travelled by foot in any case: down the slope of one hill and thereafter up the other side. There is already something in that journey itself, something we can also see in Laurits’s Kütiorg works. No, I’m not thinking of any specific views or the experience of being in a natural environment. I mean precisely the way one has to move about in the valley. You are never quite at right angles there. When going downhill, your feet are stretched out slightly in front while your body leans backwards, and when you ascend from the valley, you lean in alignment with the rising surface of the ground, your feet rise towards your shinbones, and this is how people move about and live in the valley, bent surrealistically. That displacement, that relationship that simultaneously reflects and disregards the fettering of gravitation that manifests itself in the feet and bodies of those who walk about in Kütiorg, is already present in the hanging church tower Twenty to five, (1991), yet it is also present in that peculiar procession in the work Dionysus Turns into a Dolphin (2005). Laurits expands that relationship beyond its physical posture, rather quickly arriving at chronotopes and the bending and flexing of outer space. Gravitation, which holds time together, also becomes feeble: the strata of time are folded together like sheets of wallpaper before being applied to the wall and edges that hitherto appeared to be distinct meet. The heels and the heads of history bend together. I have often admired Laurits’s bookshelf and not so much because of individual books since I never take them off the shelf. Instead, I observe the entire bookshelf as a whole – I look at it as one of Laurits’s works of art since mythologies and Jungian texts, Lao-Zi and Borges, contemporary photography and tricksters, Rushdie and calligraphy cross and intertwine among themselves in this nest of books. Laurits’s atlases of space and time form the same kind of organic whole: there are no categorisations, partitions or pages in them and in certain respects, they resemble the world view of medieval people that according to Aron Gurevitch is among other things characterised by the notion that times that follow upon one another are actually simultaneous: winter and summer, the past and the present, the moment and eternity. Up from the valley, down into the valley, body forward, body backwards, heels apart, heads together.

Kütiorg, yes. Laurits lived there together with his wife Leelo for about 12 years, building a park of paintings around his home, where guests from all over the world built beaver observation towers, a nest box for humans, an iron fern, or carried out shamanistic rituals in the tepee. Guests, intellectuals and writers, artists and poets, flocked to this place in the summers, and some regulars from the old days also came – people who were accustomed to coming here in the 1970’s and 1980’s already when the house belonged to a modernistic painter Valdur Ohakas, Laurits’s first art teacher, and his adventurer wife, their donkey and gigantic pig. Society found Laurits again. They came here to enjoy the picturesque nature of the valley, that picturesque primeval valley. They came here to swim in the lakes, to walk in the woods and to listen to stories that appeared to happen here all the time as they made campfires under the shelter of the barn. Yet all this was merely the surface layer of the relationship between Kütiorg and Laurits, the sociable exchange of impressions, scratching the surface. Kütiorg’s secrets remained hidden from that gossip, since although I don’t consider myself to be particularly esoteric, there was (and is) nevertheless something peculiar in this place. Once, for instance, I woke up to find that Peeter’s farm hand, a Gypsy named Yevgeni was sitting at the head of the bed. He sat there with self-evident self-assurance, and upon seeing that I opened my eyes, he started telling me a long story that ended with how he killed a person. Yevgeni fell silent. I was in bed under the blanket but there was no way for me to get out since the Gypsy had closed the way off. Then Yevgeni sighed. And he told me the same story over again, repeating everything practically word for word, even down to the pauses. Yevgeni had started looping. He had gotten stuck somewhere in the labyrinth and was now knocking about along the serpentine rings of his consciousness until Peeter came and sent him to work. Those kinds of strange routes are one part of Kütiorg. It’s not a very large valley, yet the orbits and trajectories that are passed through in this confined territory later prove to be many times larger in retrospect than the way they are marked on the map. Thus we can speak of a certain Kütiorg-like nomadism which not only Laurits has experienced. Many of his guests, for instance the poet Hasso Krull, who is a childhood friend of his, have described their wanderings in Kütiorg, where they manage to visit both the microcosmos and the macrocosmos during one and the same walk because

“the water mirror in the water mirror of the heavens

the pyramid in the pyramid of stems”.

Something happens there, and it also happens in Laurits’s creative work, where the tiniest structures start reflecting the largest – and vice versa. The universe is in the mushrooms, the labyrinths of decayed wood are in the Milky Way, and the ancient world conceals itself in the moss.

Laurits’s first teacher was also fond of Kütiorg. He painted it often because it really is a picturesque place: small pools and slopes, forests and treetops. Yet at some point that painter started using ever more brown paint, gloomy, muddy and threatening brown. His Kütiorg landscapes started changing. They no longer shimmered. Suddenly there was something else in them, some sort of fear or foreboding until he couldn’t take it anymore and moved once and for all together with his donkey and his adventurer wife to live in the city. Something happened there in the valley.

Once when I was playing volleyball in Kütiorg, I heard Yevgeni hiss through his clenched teeth as he watched the match, or more properly as he watched a girl: “For fuck’s sake, I’m gonna fuck that one to death.” Later on that same day I heard about a neighbour who lost his mind and had chased a fashion designer around the valley brandishing an axe. The valley drove people mad. It allowed springs to flow in itself and when people drank from those springs, they received part of that threat concealed in the bosom of the earth. It led people astray, mixed up their routes and pulled the carpet of moss out from under their feet. I have never believed that (only) the intellectual conviction that a person’s ecological footprint belongs to a cretin who is luckily destined to disappear as a consequence of his actions, that he will punish himself by building a gallows for himself now already, is behind Laurits’s Mullatoidu restoran (Dining with Worms). No. That apocalyptic feeling comes from somewhere else. It comes from that very same spring, from which also comes the fact that the colours of Laurits’s Kütiorg works grow ever darker, the horizon that is ever more constricting, the rooms and labyrinths become ever more inextricable. Once when I found myself at the Estonian Drama Theatre, I became startled as I looked at the pictures of the actors on the walls: they were photographed as if they were all already dead – faces made pale, dark eyes, and sallow skin. Yes, the author was Peeter. He had come from Kütiorg to the city to photograph the actors but Kütiorg still remained with him. This is not an apocalypse like the end of the world, of which Laurits’s latter Kütiorg period speaks. This is not a sociological or ecological message. They do indeed contain the face of death but that death is much more final, much more concrete and much more temporal than trivial matters like the collapse of civilisations. I have stood alone in Kütiorg in the middle of an August evening and when the fires were extinguished for the night and the woods became quiet, it felt for a moment as if the silent presence of death were flowing down the slopes to the bottom of the valley. I couldn’t stand it any longer. I turned around and went inside the house, where a daylight lamp shone on submarine regimen. It was supposed to prevent the sailors on submarines from going insane – and it was understandable why Peeter had hung that lamp up in the middle of Kütiorg. Everything has its ways out, even death, as Bukowski writes in one of his poems.

Yes, that is so. But for how long?

By now, Peeter has left Kütiorg.

LAURITS

There is a picture above Peeter’s worktable. A man in an undershirt – Peeter himself – sits at the kitchen table. There is a burning cigarette in the corner of his mouth and his grimace is ambivalent. Both of his hands are placed on the kitchen table and his left hand holds a knife with which he has just a moment ago cut off his right hand. That is not the first such picture. Over twenty years ago, Laurits lay down in a coffin, crossed his hands on his chest, turned the back of his head back a bit and called it his platonic self-portrait. That was a surprise. Estonian photography did not deal with those kinds of topics back then. In the 1980’s, when Brezhnevian stability that plugged up even the smallest breathing orifices was added to the poverty, greyness and monotony that already were facts of life, photography in Estonia reacted by aiming its lenses away from reality. Its focus was softened and photography concentrated on fabricated worlds, erotica or aesthetic fireworks. Laurits himself was also different – at least seemingly – until that coffin picture. His own room, intimate interiors, personal articles that are fused into still lifes with oriental stylistics – that was his heritage. Harmony was reflected in minutiae and aeonian beauty. Looking out the window of his room, everything turned more confused, the shot turned cloudy and together with the author we refused to look outside because everything that took place on the other side of the glass was simply too obscene.

Later on when convulsions began in society and times became more intense and even interesting, art in Estonia set for itself the requirement to replace contemplation with reaction – and Laurits’s creative work also changed. His pictorial language becomes more choppy and jittery. What had been his thematic core up to then branches out and is pulverised. This comes to an end only when Laurits departs to New York for a year. Yet just before his trip across the seemingly endless ocean, he photographs himself in the coffin.

I don’t know why he did that. Yet even though that picture seems to be unexpected, if it is placed in sequence with what preceded it, then it also seems logical when compared to the works that followed. A few years later, after returning from the metropolis, he founded DeStudio together with Herkki-Erich Merila, which gutted the sprouting capitalist pictorial culture with ruthless ardour. He made a few works where Laurits tried to put together a complete puzzle out of the self-portraits that had been divided up into shards but he always failed – his picture of himself always remained a fib, unfinished, and lopsided. Why? It would be appropriate at this point to recall the stork.

Peeter has spoken many times about a moment when as a little boy standing in a meadow, he met a stork and a little conversation took place between them. What exactly they talked about – that isn’t so important. The important thing is that emotional moment when Laurits for the first time encountered a world that should not have existed. A talking stork, the meadow, the summer sun – that mythological moment is perhaps the first time that we see the beginning of an endeavour. That is the endeavour to open himself up to the universe and to lose the original cause of all misery, in other words the “ego”.

Kütiorg is one of the reflections of that endeavour. Even though we see Laurits himself in only one work where he falls asleep together with his son into ancient dreams, it appears as if the entire Kütiorg period continuously tends towards the point where the concept of the individualised person dissolves in a nest formed by myths, springs and the universes known to us. The “ego” proves to be feeble, trivial and ridiculous at the crossroads of nature and culture, and the only thing that is still worth something is a tiny bit of anonymous consciousness that conceals itself like a bark beetle in the folds of spontaneous architecture in the middle of primeval forests.

And as time goes on, the more Laurits’s works become epical. Their scope starts to let go of fixed meanings and light penetrates through the wall boards and thick summer leaves, because “light strikes you like a lance / one light refracts your eye / yes indeed this kingdom / does not fit into one world” (Jaan Kaplinski). Is that a message? Is that the “theme” of Laurits’s works, his leitmotif and bellweather through all of Kütiorg: how to find hidden snake paths, trajectories that are concealed from the human eye, along which mosquitoes guide the more intelligent from among us to the threshold, which when crossed makes the categories “impossibility” and “possibility” meaningless, and peace, peace, peace is arriving? I don’t know that. I’ve never asked. Because who is there to ask? Laurits? He doesn’t exist now anymore.

An Estonian poet once wrote for a colleague’s jubilee: his poetry does not originate from the author himself or from the world around him, rather it originates from language. That is about how Laurits’s Kütiorg works could also be described. Their thematic motif is indeed often the world around the artist and the evocation that looks into the future of the apocalyptic moment that strikes that world (Veeuputus (Flood), Mullatoidu restoran (Dining with Worms)), or then – exactly like in the 1980’s – the intimate space around the artist, familiar valleys and hills, springs and larva. Yet the core of Laurits’s art has always been in pictures. That means: Laurits thinks pictorially, he combines his pictures from other pictures, and he makes pictorial that which before his works was pre-pictorial. They are those birds that are born from their own ashes. And Laurits himself is that kind of bird.